Rise of the Crawfish

5/8/2019 10:01:20 AM

By John N. Felsher

Growing up on the Pearl River, spring meant crawfish season. Starting on the first warm Saturday in February, my father and I hit the Louisiana swamps nearly every weekend until about May.

We used nets with pyramid-shaped, wired frames and baited with fish heads, chicken necks or other oily, bloody baits to catch them. We placed the nets in shallow swamp water where the mesh sat flat on the bottom, and the tip of the frame protruded above the surface. We attached bright orange, yellow, or chartreuse ribbons to the net structures to help us see them better. When running the nets, we quietly approached a “set” and lifted the net by placing a long, stout stick through the wire. We dumped the catch into an old floating ice chest that we dragged along behind us.

We started close to the road and slowly worked our way deeper into the swamp, re-baiting and relocating nets as necessary. As the morning progressed, we penetrated farther from the road with each run. When we reached the end of the line, we would take a brief break and then run the nets back to the road, where we would dump the catch into a large sack staked in shallow water. After taking another break, we repeated the process.

Back home that afternoon, the catch would be rinsed in clean water, with salt added to purge them. Inside the house, my mother prepared the seasonings and other ingredients heating in a giant pot atop the stove. After several rinses, the crawfish were ready to pour into the boiling water. As the pungent aroma of seasonings, sausage, boiled potatoes, and corn wafted all over the neighborhood, we suddenly realized how many friends we had in the immediate vicinity—including some we did not even know.

“When I moved to Mississippi almost 20 years ago, someone would have a crawfish boil every once in a while, or we would see them in restaurants,” said Dr. Susan B. Adams, an aquatic ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service in Oxford. “Now, every spring, people are selling them everywhere.”

While the tradition of eating crawfish continues stronger than ever, few people still catch their own. To satisfy “mudbug” cravings today, most people go to restaurants or buy commercially raised or caught crawfish, either alive or already boiled.

“The custom of eating crawfish is no longer confined to Louisiana,” said Dr. Robert L. Jones, a biologist with Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks’ Mississippi Museum of Natural Science. “People are starting to eat them all over the South. Many people on the Pacific Coast also eat crawfish, but the crawfish there are in a completely different family from Mississippi crawfish. They are more closely related to Asian species than ones in the South. Crawfish are everywhere in Mississippi, which is among the top states in the country for the number of different species. Mississippi also has at least two species of dwarf crawfish. A big adult dwarf craw-fish is less than a half-inch long.”

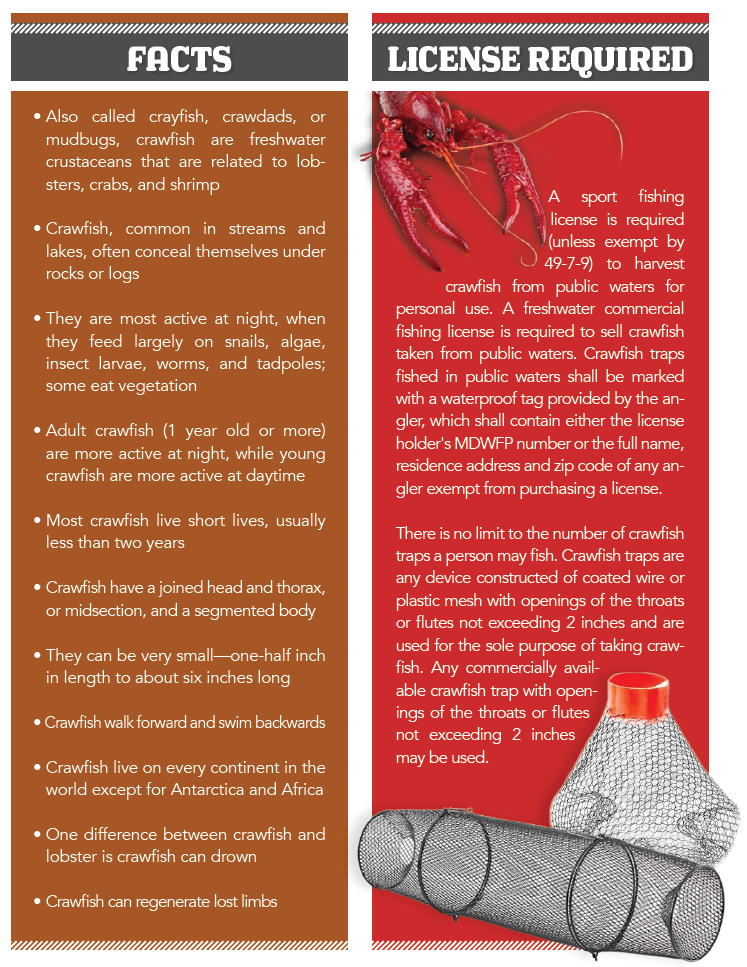

More than 330 crawfish species populate North America. Crawfish live in clear, mountain streams flowing through the Pacific Northwest, desert impoundments in the Southwest, rocky Northeastern lakes and, of course, Southern swamps. Even more species populate every continent except Antarctica. They thrive in many different habitats such as lakes, rivers, swamps, roadside ditches, and even dirt.

“Crawfish are native to all the continents except Antarctica and mainland Africa, but some species live in Madagascar,” Adams said. “Mississippi is near the top of the list of states for its diversity of crawfish. We don’t have an exact number of species in the state, but it’s probably about 63. Many species only occur in Mississippi and nowhere else in the world. We’re still finding new species regularly, including some in Mississippi. I’m working on describing a potential new species that we first found in the Dahomey National Wildlife Refuge in Bolivar County.”

Most people only recognize two types of crawfish: live or boiled. People in Mississippi and across the South normally eat three crawfish species: red swamp and two species of white river. Among the biggest species in the state, red swamp crawfish are slightly larger than white river crawfish. They generally show more reddish coloration than white river crawfish.

“I’ve known people who spent their entire lives fishing in Mississippi,” Adams said. “I’ll ask them how many crawfish species are here and they usually say ‘one.’ Red swamp and white river crawfish occur all over the state, but are most common in the Delta and along the coast. Red swamp crawfish have been introduced all over the world as food, including in mainland Africa.”

Red swamp crawfish naturally range from northern Mexico up to New Mexico, across the Gulf States to the Florida Panhandle and up the Mississippi River drainage to Illinois and Ohio. They have been introduced in many other states, including Hawaii. The aggressive crustaceans can become pests in some areas because they multiply rapidly, can live practically anywhere, and displace native species. Some state fisheries departments even try to eradicate them within their borders. As recently as July 2018, about 2,000 pounds of live, red swamp crawfish—illegal in Michigan—were seized at the Canadian border. The crawfish were taken to a lab at Michigan State University, frozen, then incinerated.

“The red swamp crawfish is getting a notorious reputation as an invasive species wherever it’s introduced,” Jones said. “Once it gets established, it can be a problem for native species.”

White river usually make up about 20-30 percent of the more than 150 million pounds of crawfish consumed annually along the Gulf Coast. As the name indicates, white river crawfish look lighter in color with longer, narrower claws than their red cousins. The two species share the same habitat and much of their same natural ranges. Native to wetlands from east Texas to Alabama and northward up the Mississippi River Valley, white river craw-fish have been introduced elsewhere.

“During the summer breeding season, red swamp crawfish have a lot of red on them,” Jones said. “In the winter, they turn brown. White river crawfish can be very dull colored all year long. Red swamps also have bumps all over them. Both are most often found in swamps, ponds, and ditches. If their pond dries up, they will construct a temporary shelter burrow in the mud.”

Red swamp and white river crawfish typically live in fresh water, but occasionally dig holes. However, some species dubbed “primary burrowers” spend most of their lives underground. Mississippians commonly see “crawfish chimneys” created by burrowers sticking up in their backyards or other places with moist soil. When digging a hole, burrowers push wet dirt above the ground to make mud cylinders. Burrowing crawfish infrequently show up in platters of boiled crawfish, but look completely different from either red swamp or white river crawfish.

“Most of the crawfish that make burrows in everyone’s yards are in a different genus than red swamp and white river craw-fish, although those species do burrow and make chimneys also,” Adams said. “People can eat any species of crawfish, but the burrowers have very small tails and big, thick claws. They don’t have as many spines as species that live in the water where fish and other creatures can eat them. Burrowers also have smaller eyes since they live underground.”

Burrowers rarely leave their holes except to find food or a mate. On warm nights, though, people might spot one at the top of its burrow taking in the refreshing evening air. Some astonishingly extensive burrows go down more than six or seven feet deep. Many a young boy ex-pended countless hours dropping pieces of meat on a string down crawfish chimneys trying to catch the cunning crustacean lurking below the ground.

“A primary burrower will never go in open water,” Adams said. “Some areas in the state, like around Starkville, have unique burrowing species that only occur in those soils.”

Practically every bird, animal, or fish capable of taking on the armored crustaceans enjoys slurping the succulent morsels, including some insects and their aquatic larvae, like dragonflies. Some predatory species even depend upon catching crawfish in their burrows.

Now, we can add even more people to that predatory roster. Whether bought or caught, sitting down to eat a steaming mess of mudbugs surrounded by friends and family makes a pleasant spring tradition loved by many people—and the number keeps increasing beyond the Louisiana borders every year.

John N. Felsher is a freelance writer for Mississippi Outdoors.