10/22/2019 3:04:27 PM

By Sherry Lucas

CLARKSDALE — John Ruskey strolls along the bank of the Sunflower River, scoops up a cottonwood leaf, glances down at its delicate veins, and traces the Father of Waters’ path in his palm.

“This is like the Mississippi River right here. Here’s the Ohio and the Arkansas, the Missouri …,” says the river guide, canoe builder, writer, musician, and artist. “The river is the circulatory system of our nation.”

It is certainly in Ruskey’s blood — a harmonious give-and-take pulse since late 1982, when he and his best friend, Huck- and Jim-style, floated down the Mississippi River on a home-built, 12-by-24-foot raft. They made it five months and 1,500 miles before a crash just past Memphis left them muddy refugees on a river island. “That was my first time in the state of Mississippi.”

Second time was in 1991. The mud and smell of the Mississippi River was still fresh in his nostrils, he says. Then a traveling musician, guitar and accordion in hand (and an Austin, Texas, destination in mind), he felt Clarksdale’s tug as a stopover before settling down. He stopped and settled.

Heeding the Call

As Delta Blues Museum curator in the 1990s, Ruskey’s blues education program brought children and master musicians together to continue the Delta blues tradition. But the river’s music continued to call him. Museum visitors’ Mississippi River curiosity was part of the nudge, too, behind his Quapaw Canoe Company’s start a little over 20 years ago. Ruskey started taking people out on the river, one at a time, in his two-person Grumman canoe.

“There’s such a worldwide interest in the Mississippi River, and anyone traveling to this part of the country is going to want to see the river,” he says. Up close. “They want to touch it and feel it. Swim in it.” He left the museum, hung out his shingle and the business grew slowly, by word of mouth and folks searching him out.

“There’s such a worldwide interest in the Mississippi River, and anyone traveling to this part of the country is going to want to see the river,” he says. Up close. “They want to touch it and feel it. Swim in it.” He left the museum, hung out his shingle and the business grew slowly, by word of mouth and folks searching him out.

In previous lives, Quapaw Canoe Company’s downtown building housed a tire-recapping factory and a Studebaker dealership. Ruskey’s endeavor started in “the cave,” his nickname for the basement around back, right on the Sunflower River’s bank. That was home base for years. He and his wife bought the whole building a decade ago, and the company’s interpretive center, gear storage, and canoe shop sprawl across the Sunflower Building’s 18,000 square feet.

In his office, Ruskey’s conversation is as peppered with river history and lore as his conference table is full of its finds. Coral, driftwood, a deer skull, and a vine-wrapped stick of beaver-chewed willow catch the eye. So do his watercolors of a Mississippi map turtle and the topographic swirl of greens and golds on its shell that echo his richly colored maps.

He holds up a winged piece of driftwood. “Doesn’t this look like it could just fly away?”

A Way in the Wild

“I feel connected, wherever I am in this world if I can get outdoors,” says Ruskey, who grew up on the edge of Arapaho National Forest in the Colorado Rockies. That was his playground.

“Since I was a kid, I’ve always been a little bit of a wild one,” he says, captivated by water’s magic. He likes to imagine the spark — likely spotting a bird floating by on a piece of driftwood — that led to the development of canoes for transport in ancient times. A Langston Hughes poem comes to mind, about rivers older than the flow of human blood in human veins. “Surely there are canoes paddling in those same veins, somewhere in all of us,” Ruskey says, “because it goes back thousands of years.”

The spark for his own canoe craft education was a 1998 call for a weeklong river trip for 17 kids from Denver. “Sure, I can do that,” Ruskey answered, despite his one-canoe inventory and one-at-a-time excursions. A research deep dive turned up the voyageur canoe tradition, from the French fur trade in Canada and the Great Lakes, and master canoe builder Ralph Frese, then in his late 70s.

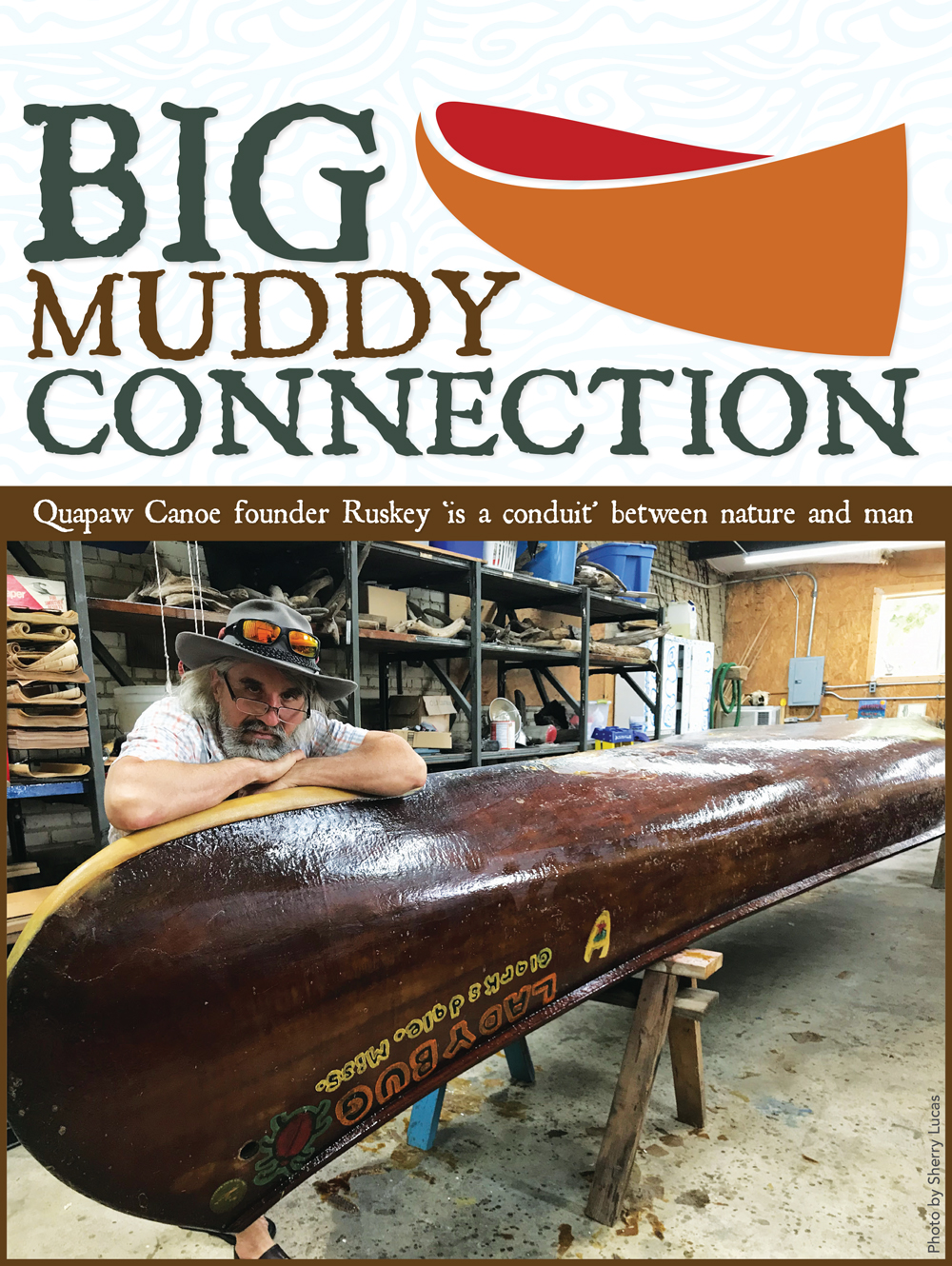

He reminded Ruskey of another master, blues artist Johnnie Billington, who had mentored him on keyboard and guitar. “Like Mr. Johnnie, Ralph was an old-time teacher. You had to learn yourself and you had to demonstrate your passion for it before he would share anything with you.” Ruskey worked through a list of books, then returned to learn, and Frese guided him through the construction of the 27-foot cypress canoe, The Ladybug.

A year later, Ruskey circled back to the Denver school to book the date. One of its students even helped him finish the vessel, becoming one of Ruskey’s first apprentices. The Ladybug held most of the kids, with a few smaller canoes carrying teachers and skilled students.

“This one canoe became the mothership on the Mississippi, and we still call her ‘The Queen,’ because she has outlasted all the other canoes and is still a functioning vessel.” The big canoe can hold 11 people who have never paddled before. Ruskey says teach them a basic motion, with a canoe captain at the rear to guide, “and set off on the biggest and arguably most dangerous river in North America — the mighty Mississippi — and safely take them on a river journey, out to an island, and back to shore.”

They started at the foot of Beale Street, christening Ladybug with a bottle of champagne and setting off downstream. The sense of accomplishment? So joyful, he says, “I felt like the first man on the moon.

“That school ended up sending kids for years afterward.”

Fostering Future River Stewards

Ruskey’s Mighty Quapaw Apprenticeship Program also started with a need. Young people were drawn to Quapaw from its earliest days. Anytime Ruskey worked on a canoe, neighborhood kids would stop and watch, sometimes for hours at a time. “Kids being kids, eventually they wanted to try it themselves. … By and by, I realized that I could do the same thing that Mr. Johnnie did.

“You learn by doing it … by mastering specific skills, and taking care of yourself, and living healthfully but also joyfully. Mr. Johnnie called his last project The Health and Happiness Ranch,” after the two things he believed in most, Ruskey says. That is the same philosophy for Quapaw Canoe Company. “You’ve got to take care of yourself if you’re going to take care of other people … and if you’re going to take care of the river.”

Mighty Quapaw Apprenticeship Program: A hands-on learning experience focused on developing skills for better health for yourself, others, and the environment. Photo by John Ruskey

To hear Ruskey talk about the Mississippi River is to get lulled into its lure. He counters the fragmented, pieces-and-parts style of life on land with the smooth, contiguous fashion of time on the river. Each move connects to the other and connects people to each other and to the environment all around. “With the apprenticeship, that worked beautifully.” Many youths had trouble getting enough sleep at home. “When we went out on the river, one of the first things they did was catch up on sleep.”

That happens with clients, too. “Time and time again,” he says, “one of the reoccurring things we hear is, what a great sleep they had.”

He has seen a lot of hunched shoulders smooth out and tight lips melt into smiles, “and a lot of repeat customers because of that.” Touching the water, feeling the mud squish between toes, sleeping on a sandbar under the stars, spotting spectacular creatures — that does the trick.

“Most people come back glowing. You can see it in the before and after pictures.”

Maintaining Traditions

The Ladybug awaits refinishing in Quapaw’s canoe shop. “Queen of the Mississippi,” Ruskey says, giving her a fond pat. Rough, peeling layers of old varnish scar her hull. “We’re going to strip off all the varnish and give her a clean dress to wear.” A 29-foot voyageur canoe, Dragonfly, stretches out on a form alongside her, ready for a fiberglass seal. The smooth, bare wood and sensuous curves make a passing touch irresistible.

“The canoe is one of the most beautiful shapes ever because it’s art and it’s function. And, if you take out any single piece in one of these canoes, it would fall apart and become dangerous to use in the water. The integrity is dependent on everything working together.”

Outside, a cottonwood log is a dugout canoe in progress, bearing the blade marks of students from the Griot and Spring Initiative youth programs. Dugout canoes are an educational program for Quapaw, which built one for the Carnegie Library, and two for the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Expedition.

Ruskey apprenticed with Chinook elder and master canoe builder George Lagergren in Willapa Bay, Washington — “Grandfather George” to Ruskey — in the craft. Using the Chinook tradition, the project challenges kids to find the spirit in the log and bring that out in the canoe. They would sit quietly by the log with notebooks, drawing ideas that came to mind, he says. By vote, the kids dubbed it Catfish. Dugout canoe building generally takes thousands of hours, Ruskey says, and the multi-year project involves 144 kids working a couple hours per month, with completion likely another year away.

Nature's Inspiration

“The river has become my life, and everything that I do is somehow connected to it, including my marriage and my family and my work, my art — it’s everything,” Ruskey says. With his wife, Sarah Crisler-Ruskey, now director of the Harrison County Library System, he is back and forth between Clarksdale and Gulfport. “I have one foot now planted in the salty water, but it’s not far from the mouth of the Mississippi down there.” They have a daughter, Emma Lou, 11.

Ruskey, 55, might be the youngest yet to receive the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters’ Noel Polk Lifetime Achievement Award, recognizing his writing, art, and music, as well as his environmental efforts, work with youth, and Mississippi River knowledge. Chuckling, he doffs his hat to show a headful of gray hair, like a proof of age.

“I’ve always been kind of a creative type,” he says. Yet, art was an undercurrent until he spent a lot of hours on the river with a notebook. “Originally, the river kind of tricked me into it. I became a sketch artist, trying to understand the flow of the water, from the banks of the river.” Pens and pencils evolved to watercolor. His writing, he says “is all about opening the flow of what I’m experiencing.”

Ruskey’s “Rivergator” — rivergator.org — maps the entire 1,100-mile trail of waters of the Lower Mississippi River, St. Louis to the Gulf of Mexico. Ten identified sections offer a mile-by-mile description of the river, mostly oriented toward paddlers, to help them find campsites and landings, and enjoy safe travels. “On top of that, I tried to do a little bit of Mark Twain, and help paddlers learn to read the river,” he says, sharing secrets he spent so much time learning.

“It’s almost like he’s a conduit between nature and everybody around him,” says Grenada artist Robin Whitfield, Ruskey’s first mate on a recent painting expedition to Horn Island. She had been out with him on river day trips for years, but the gulf waters and weeklong trip were a first. Whitfield marvels at the almost spiritual connection felt with fellow paddlers, like birds flying or fish swimming, as they journeyed to the island by canoe. She appreciates Ruskey’s small ceremonies and thoughtful, intentional details that fostered “so many layers of connection.”

In typical river fashion, he opens the flow. “Modern civilization has grown away from connections to the Earth,” Ruskey says, “but we always have been and we always will be deeply connected to the wild power of nature.”

Sherry Lucas is a freelance writer for Mississippi Outdoors