Gators on the Move

7/20/2018 10:30:09 AM

By Ricky Flynt

MDWFP’S TAGGING PROGRAM MONITORS THE ALLIGATOR PROGRESS IN MISSISSIPPI

Many people remember the American alligator as an endangered species during the 1960s and ’70s. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had list-ed alligators under the Endangered Species Act in 1967, which gave alligators protection by state and federal wildlife conservation agencies across the southeastern United States.

Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks (MDWFP), then known as the Mississippi Game and Fish Commission, actively participated in the conservation, and eventual recovery, of the American alligator.

Early in the recovery process, the Mississippi Legislature and the Commission on Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks enacted laws and regulations to provide protection and charged MDWFP with enforcing those laws and creating an Alligator Management Program. While these were necessary steps, few things were more vital to the speedy recovery of Mississippi’s alligators than the release of wild-caught alligators into unoccupied habitats. During the early 1970s, MDWFP conservation officers and wildlife biologists made numerous trips to Rockefeller Refuge in southwestern Louisiana to obtain live alligators from Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF). Over several years, alligators were captured and transported to suitable Mississippi habitats in pickup trucks and livestock trailers. LDWF eventually donated more than 3,000 alligators to Mississippi. These relocation efforts proved fruitful as Louisiana alligators found a comfortable home in Mississippi and began to reproduce and flourish in areas where they rarely had been seen for decades.

MDWFP began conducting survey routes along waterways throughout the state to monitor alligator populations early in the restoration. The resulting data showed a slow but steadily increasing trend over the next 30 years. By 1987, populations had recovered sufficiently, and the American alligator was downgraded from the endangered listing, making it one of the first recovered species under the Endangered Species Act.

By the 1990s, some populations located near developed areas had become so abundant that nuisance alligator com-plaints became commonplace. While some alligators had to be euthanized (because they displayed a lack of fear toward humans), a significant number were relocated to more remote swamps and waterways in hopes they would establish a new residence in more rural environments. Relocation distances varied depending upon availability; some were only a few miles away while others had to be moved more than 30 miles.

Eventually, conservation officers began to notice that some areas became routine for nuisance complaints. Similar-sized nuisance alligators regularly would have to be removed from the same locations. Officers started to theorize that some of these reoccurring complaints were actually the same individual alligator returning to its original location. However, the ability to identify positively one alligator from another was nearly impossible without any obvious marks or characteristics.

It soon became clear that some alligators had a keen ability to find their way back to their original capture location, so that, in some instances, MDWFP was repeatedly relocating the same alligators. This led MDWFP to develop a formal alligator-tagging program in 2007. The program had the dual purpose of documenting growth rate and movement information, while also evaluating the effectiveness of alligator relocations.

MDWFP, with help from agent alligator trappers, would capture alligators, place uniquely colored and numbered tags on the tails, and attach metal clip tags on the webbed portion of their hind feet. Officials recorded GPS location, sex, length, and other biological measurements of each alligator before releasing it back where it was captured. Some nuisance alligators also were tagged and relocated various distances from their original capture location to test whether they were finding their way back home. It did not take long to verify this theory. In 2007, the first alligators were tagged on March 30 and, by April 27, MDWFP had its first recapture of a tagged and relocated alligator. Tag Yellow 70, a 79-inch-long male captured at Timberlake Campground on the Ross Barnett Reservoir, relocated 18.9 miles up the Pearl River. He found his way back to the Timberlake Campground in less than a month.

Since 2007, the tagging program captured, tagged, and released almost 800 alligators. The vast majority were released at their original capture location, but dozens were relocated and later found their way “back home.” In one instance, an 8-foot female traveled seven miles back home in just five days.

In other cases, tagged alligators that have not been relocated also have been documented traveling unusually long distances. One such alligator, White 4, a 92-inch male, was captured in Warren County at Tara Wildlife on March 18, 2009, and then recaptured on April 11, 2012, near Lake Providence, La., by an LDWF nuisance alligator trapper.

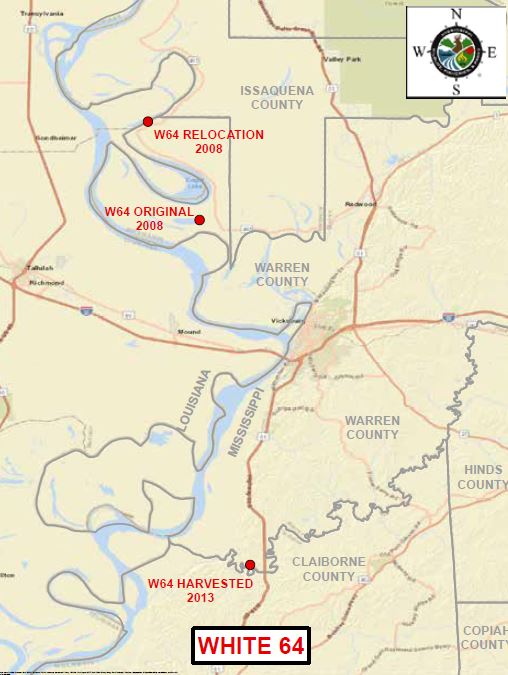

White 4 had grown 19 inches and traveled a straight-line distance of 30 miles. Another alligator, White 64, was harvested by a permitted alligator hunter during the 2013 alligator hunting season. White 64 had moved 67 river miles 50 months after being captured and had grown an incredible 51 inches in only five growing seasons.

The tagging program has provided useful information about the relocated alligators’ habits. It is interesting to be able to document the basics of alligator growth and movement in the wild by simply tagging, identifying, and recapturing individual animals.

Such records like White 4 and White 64 are unusual, but the vast majority of recaptured alligators have been within one to three miles of their original capture location, regardless of their size. MDWFP continues to obtain recapture information, most of which comes from hunter harvest reports. On average, about 10-15 tagged alligators are reported harvested by Mississippi alligator hunters each year. Each hunter who reports the capture or harvest of a tagged alligator receives a certificate and the historical information about the alligator. It is just another way that hunters are doing their part to provide vital information to wildlife biologists so we can better understand the wildlife we manage. For more information about alligators and alligator hunting, visit www.mdwfp.com/alligator.

Ricky Flynt is the Alligator Program Coordinator for the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks.