2/14/2020 4:11:46 PM

By Sherry Lucas

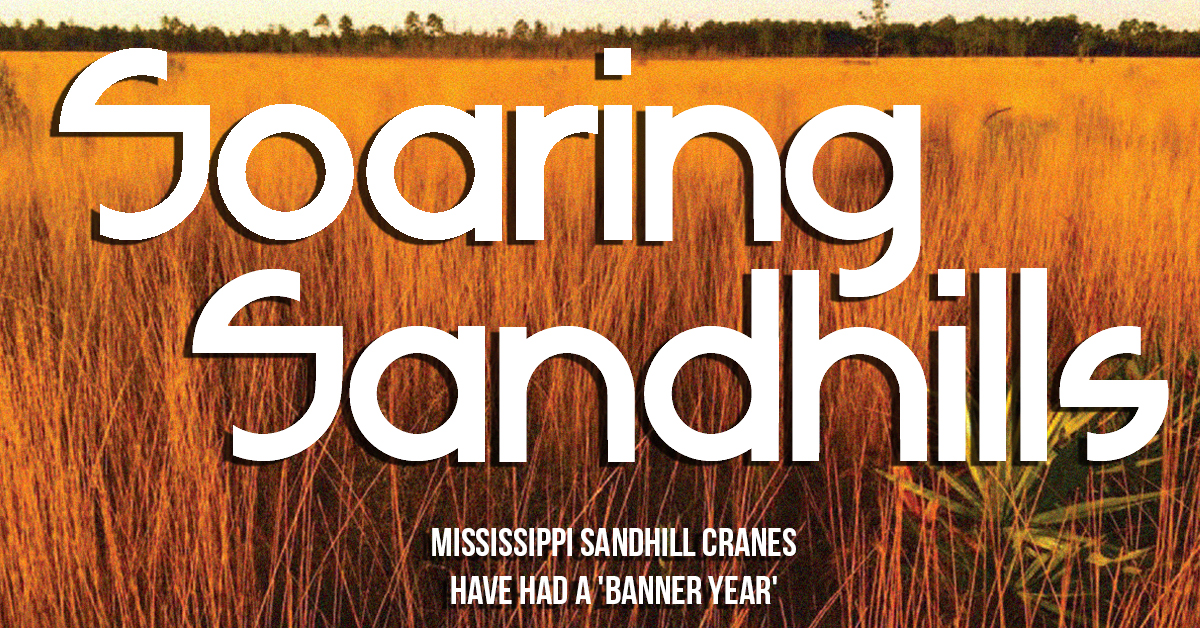

North Valentine Savanna / Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge (photo by Scott Hereford - USFWS)

A bumper crop of fledglings is the biggest news in years for the endangered Mississippi Sandhill Crane and its namesake wildlife refuge in Jackson County. The 15 chicks fledged from the population, after several years holding at five or six, represents a 250% increase in chick survival.

“This is a banner year. It’s one of the milestone moments in crane conservation history,” says Scott Hereford, a senior wildlife biologist at the Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge. “There’s a 90% chance that, once they fledge, they will make it to the age of independence.”

Mississippi Sandhill Crane (photo by Darren Rothberg - USFWS Intern)

The refuge, headquartered in Gautier, has reached another milestone, with a population increase from 30 to 40 at its 1975 start to more than 140 now, and the number of nesting pairs growing from five or six at the beginning to 40 breeding pairs this season.

The endangered Mississippi Sandhill Crane is a subspecies of Sandhill Cranes. Sandhill Cranes are found all over North America and parts of eastern Russia and fly south for the winter, but the Mississippi Sandhill Cranes are non-migratory, as are sub-populations found in Florida and Cuba. The first mention of Mississippi’s non-migratory population was in wildlife biologist Aldo Leopold’s Mississippi Game Survey in 1929, with the description as a subspecies coming in 1972.

“Even at that time, they were restricted to Jackson County. They had been mostly hunted out elsewhere,” says Nick Winstead, an ornithologist at Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks’ (MDWFP) Mississippi Museum of Natural Science (MMNS).

“People like to hunt and eat Sandhill Cranes,” Winstead says, recalling his work in south Louisiana, putting transmitters on Sandhill Cranes that overwinter there. “I talked to one of the guys that lived there, whose property they were on, and he told me that they were the filet mignons of the sky.”

While migratory Sandhill Cranes are hunted in some states, endangered non-migratory subspecies are protected by federal and state law.

Though large birds, Mississippi Sandhills stand a bit shorter than some Sandhill Cranes (about four feet tall with a six-foot wingspan). They sport the darkest gray plumage of any of the subspecies, which makes their white cheek patch stand out. A striking red crown tops the head. They typically form longtime pair bonds, and their loud, rattling calls make a sound some describe as prehistoric.

Tall, skinny, and elegant with their long legs and necks, the Mississippi Sandhill Cranes are occasionally mistaken for Great Blue Herons. According to Winstead, herons lack the red cap and will often sit with their necks hunched. Cranes are typically erect with their necks extended (cranes also keep their necks extended in flight).

“Wherever cranes are found … people are fascinated with them because of their regal carriage, large size, loud and distinctive vocalizations, strong and long-lasting pair bonds, and interesting repertoire of behaviors,” Hereford says. “They are symbols of long life and happy marriage in many parts of Asia, for example.”

The rarity of Mississippi Sandhill Cranes — one of the rarest bird populations in North America with a small localized range — makes them even more intriguing.

“Historically, it’s believed that there was a non-migratory population of Sandhill Cranes scattered all along the Gulf Coast, from Texas to Florida,” Winstead says. Habitat loss from development, fire suppression, and pine plantations contributed to dwindling numbers.

As with most wildlife management, habitat loss is typically the top cause of wildlife species decline. The main objective of the Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge, which has about 19,300 acres in three main units in the Gautier and Ocean Springs area, is to restore and maintain native habitats. For the cranes, it is about restoring and maintaining the coastal wet pine savanna that the birds have adapted, Hereford says. The soggy, open prairies in Jackson County are grasslands with scattered pine trees, mostly longleaf pine, and also pond cypress.

Mississippi Sandhill Cranes (photo by Amanda Phillips)

“It’s a very unique and diverse ecosystem. …The plant diversity at the ground level is among the highest described anywhere in the world,” says Hereford. “There can be 30 to 40 different species of plants, per square meter, on the ground, including wildflowers, orchids, and many types of carnivorous plants such as pitcher plants and butterwort.” Only 2-3% of the original range of these wet pine savannas in the Southeast remains, making it one of the rarest ecosystems in North America.

That landscape, teeming with diversity, is a draw, too, at the refuge, which welcomes more than 10,000 visitors annually. Late fall, winter, and early spring are the best times to visit. In the fall/winter season, the popular Crane Tours catch the best time to see the elusive Mississippi Sandhill Cranes when they are more active (visit https://www.fws. gov/refuge/Mississippi_Sandhill_Crane/ for details). The refuge’s visitor center offers displays and a gift shop on adjacent grounds, and the refuge’s two nature trails offer the chance for wildlife observation and nature enjoyment.

Nest and eggs / Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge (photo by Scott Hereford - USFWS)

“In the last year, for the first time, cranes can be frequently seen right behind the headquarters of the visitor center,” Hereford says. Two juvenile females, released behind the headquarters in early 2019, stayed close, and other pairs come in. “That was one of the objectives of the releases this last year, to try and populate this area near the headquarters.”

At the refuge, other grassland birds find a welcome respite, too, such as the rare Henslow’s sparrow (a quarter of the world’s population overwinters there) and the yellow rail (a small marsh bird that is also declining). For the fifth year, the refuge is part of a translocation program for the endangered Mississippi gopher frog, one of the rarest amphibian populations in North America.

For eons, frequent fires — every two to three years — naturally maintained the grassland-dominated landscape. Now, prescribed burning is the mainland management tool, with aims to burn 5,000 to 6,000 acres a year. Otherwise, grasslands would slowly turn into a shrubby tree jungle, and native grasses, plants, and birds keyed into open areas would start disappearing, Hereford says.

In Jackson, MMNS features a diorama of Mississippi Sandhill Cranes at the nest, offering a close-up view. Mississippi Sandhill Cranes were close to being wiped out in the 1970s. A captive breeding program was developed, and by 1981, captive-reared juveniles were being released to supplement the refuge’s existing population. “That’s continued annually since then,” Hereford says. “So, this release program/supplementation program is the largest and longest in the world.”

The cranes lay two eggs but rarely raise more than one chick. The chicks can walk within a day but remain tied to the nest for about 75 days.

Newly hatched chick and pipped egg / Mississippi Sandhill Crane National Wildlife Refuge (photo by Scott Hereford)

“When they leave the nest for good, that’s when they’re considered to be fledged. That first 75 days is a critical period,” Winstead says, when they are tied to one location and are more vulnerable. After that, they still stay close to the parents, learning to feed and live, up to the next nesting season. “The adults are really putting a lot of effort into this chick … longer than the average bird, and that’s why they don’t lay that many eggs.”

Mississippi Sandhill Cranes can live 20 to 30 years in the wild, and it can take them five to six years to nest. Credit the accumulation of years of work with state, federal, and non-government partners, restoring and maintaining habitat, releasing birds to slowly build the population, and good conditions, for the “bang-up, chick-rearing year,” Hereford says. “Of the 130-plus Mississippi Sandhill Cranes, well over 90% are captive-reared, or their young, or their grandbabies. That’s who’s out there now. … They’ve actually been surviving and nesting.” Chick survival has been the issue, with the concern some captive-reared birds missed behavioral things wild birds managed better.

“With 15 chicks surviving, that is really enough to replace annual mortality. So, looks like they’re figuring it out. It’s just taking longer than we thought,” Hereford says “We will see if this is just a one-shot deal that it jumped up to 15. Hopefully, it’s going to stay up near there.”

Objectives of 130 to 150 cranes and 30 to 40 nesting pairs are insight. Maintaining 12 to 15 fledglings a year over several years would be self-sustaining, and the refuge could pull back on releases.

The refuge is working with its sister refuge, Grand Bay National Wildlife Refuge headquartered in Moss Point, where habitat restoration continues following impact from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and with the Grand Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

With the possibility of several thousand acres restored back to coastal wet pine savannas in the next 5–10 years, a plan is in the works that could release Mississippi Sandhill Cranes there for a small, additional breeding population.

Sherry Lucas is a freelance writer for Mississippi Outdoors.