Hemorrhagic Disease & the White-tailed Deer

According to the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study (SCWDS), hemorrhagic disease (HD) is "the most important infectious disease of white-tailed deer." The significance of this statement is difficult to grasp, especially when diseases like anthrax and chronic wasting disease are considered. To document and illustrate the distribution and impact of this viral disease, SCWDS reported that, from 1980 - 1989, HD-related white-tailed deer illness or death was documented in 875 counties within 31 states. The geographical distribution of HD included most of North America, ranging from the southeastern regions of Florida to Washington.

Most wildlife disease researchers believe that HD has negatively impacted deer populations for most of the 20th century. The landmark 1955 outbreak in New Jersey led to the initial viral isolation and definitive diagnosis of the disease.

Cause & Transmission:

Hemorrhagic disease commonly occurs in 2 forms, epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) and bluetongue (BT). The viruses that cause HD are in the genus Orbivirus. There are two serotypes of EHD virus (serotypes 1 and 2) and six serotypes of BT virus (serotypes 1, 2, 10, 11, 13, and 17) that occur in the United States. All except BT 1 have been found in Mississippi deer.

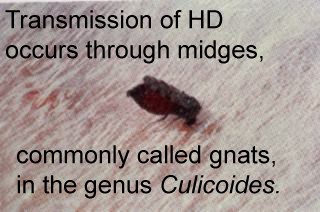

Transmission of HD occurs through biting midges, commonly called gnats, in the genus Culicoides. The most important species is thought to be Culicoides variipennis, but the disease also may be spread by other species of Culicoides. The disease usually occurs in late summer and early fall, in response to the increasing occurrence of the midge vectors. Animals with symptoms of HD may be found well into winter, and subsequently harvested by hunters, resulting in questions concerning their condition. Transmission of HD typically ends with the onset of freezing temperatures.

Symptoms:

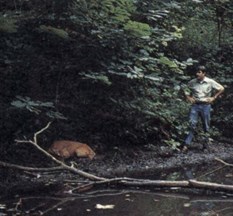

Since the peak infection period occurs when few people spend time in the woods, even severe outbreaks may go unnoticed initially. More commonly, hunters will find carcasses or notice recovering animals during the hunting season. Occasionally, in late summer, someone will observe a sick deer or a carcass in or near water.

The observable signs of infection vary with the three forms of HD: peracute, acute, and chronic. The peracute form, characterized by its rapid onset, is the most dramatic. Deer may exhibit a loss of awareness of their surroundings, very high fever, difficulty in breathing, swelling of the head and neck, and the bluish coloration and swelling of the tongue that makes "bluetongue" a common name of the disease. Death from the peracute form often occurs within 24 hours. In especially severe cases deer may die suddenly, even before any observable signs are evident.

With the acute or classic form of HD, deer live somewhat longer. In addition to swelling associated with the peracute form, these animals may show hemorrhaging in the heart, rumen, and intestines. They may also have ulcers on the tongue, dental pad, palate, rumen, and omasum.

Many hunters are familiar with the hoof sloughing associated with the chronic form of hemorrhagic disease because the condition frequently persists into the winter. An interruption of growth, resulting from high fever, often causes the hooves to appear broken or ringed. In extreme cases the tips of the hooves will actually slough off. Debilitated deer may crawl on their knees or even push along on their chest, resulting in additional lesions on those areas. Although less frequently noticed, the lining of the rumen may also become ulcerated, scarred, or even eroded. The deer's ability to absorb nutrients from ingested food is compromised when significant amounts of papillae, the finger-like projections on the rumen wall, are lost. Emaciation can result, even in the presence of ample food resources.

Public Health Significance:

Hemorrhagic disease poses no direct health risk to humans. The disease is not transmissible to humans by contact with infected deer, consumption of venison from infected deer, or being bitten by midges carrying the viruses. However, deer may develop bacterial infections or abscesses resulting from the disease and venison from these deer may not be suitable for consumption. Furthermore, we do not recommend the consumption of any deer that has died of unknown causes.

Domestic Livestock:

Cattle, sheep, and goats are susceptible to HD, but the disease is quite variable depending on the host species. In sheep, for example, BT seems to be the most important, causing severe disease, while EHD does not. Cattle, which are susceptible to both EHD and BT viruses, seldom exhibit any signs of sickness. There is little known about the "reservoir status" of HD. It is not known whether the disease is perpetually harbored in deer and then transmitted to other deer and livestock when vector and climatic conditions are suitable, or if livestock populations harbor the disease until conditions are conducive for transmission.

Overpopulation:

The relationship between deer population density and the rate of occurrence of HD is not fully understood. The disease is not considered to be classically density dependent, because the infection rate does not increase directly with the deer population. Obviously, the occurrence and prevalence of the midge vector contribute to the timing and rate of infection. It is logical that the higher the density of the deer herd, the greater the opportunity for the virus to be transmitted from deer to deer via midges. Perhaps the most important aspect of the disease-population relationship is the physical condition (body weights, energy reserves, etc.) of the deer herd. The effects of the disease will be more pronounced in overpopulated herds with diminished physical conditions. Survival rates are typically lower for nutritionally stressed, infected deer and recovery time for those that survive will be greater.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis:

A strong tentative diagnosis can be made by physical examination of a clinical animal. However, the disease can only be confirmed by virus isolation, which is a laboratory procedure that requires collection of suitable tissue or blood from an infected animal immediately after death. Virus isolation and identification capability diminishes rapidly after death; therefore, an animal that is suspected of having HD must be examined by a trained biologist or veterinarian within hours of death.

Resistance to the Disease:

Hemorrhagic disease is not distributed uniformly throughout the range of white-tailed deer. Outbreaks in northern latitudes are uncommon, but when they do occur infection and mortality are severe. In southern regions outbreaks are common, but the effects are generally mild, or even unapparent, indicating possible natural resistance to clinical levels of infection. Experimental infection of deer from northern and southern populations produced markedly different results. Clinical disease was mild or completely absent in the southern deer, while mortality in northern deer was 100% from one strain of the virus and 20% from another. This demonstrates that populations frequently exposed to the viruses apparently develop genetic resistance to HD through the processes of natural selection. Deer that have suffered from the chronic form of the disease develop an immunity to that particular strain of the virus, but are still susceptible to the other strains. This immunity can be detected through testing of serum collected during herd health evaluations.

Understanding that geographically different deer populations have different levels of natural resistance to HD has obvious management implications. Translocation of deer from northern to southern latitudes will likely result in high mortality of the individuals involved. A less apparent, but potentially more serious problem is that if northern deer translocated to the South do survive and pass along their genes, this may actually contribute to diluting the resistance that has evolved in our native southern deer herds.

Mortality:

Hemorrhagic disease is the most important endemic infectious disease in white-tailed deer in the Southeast. Outbreaks occur every year and are highly variable in severity. Mortality of the population is usually less than 25%, but may be 50% or greater. However, these percentages are hard to diagnose, as many deer that die from the disease are never found.

Reporting:

Even though HD occurs most commonly during late summer and early fall, hoof sloughing may be observed throughout the year. If you observe a deer with any of the symptoms listed in this article, report it immediately to any of our three Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks regional offices or our main office in Jackson.