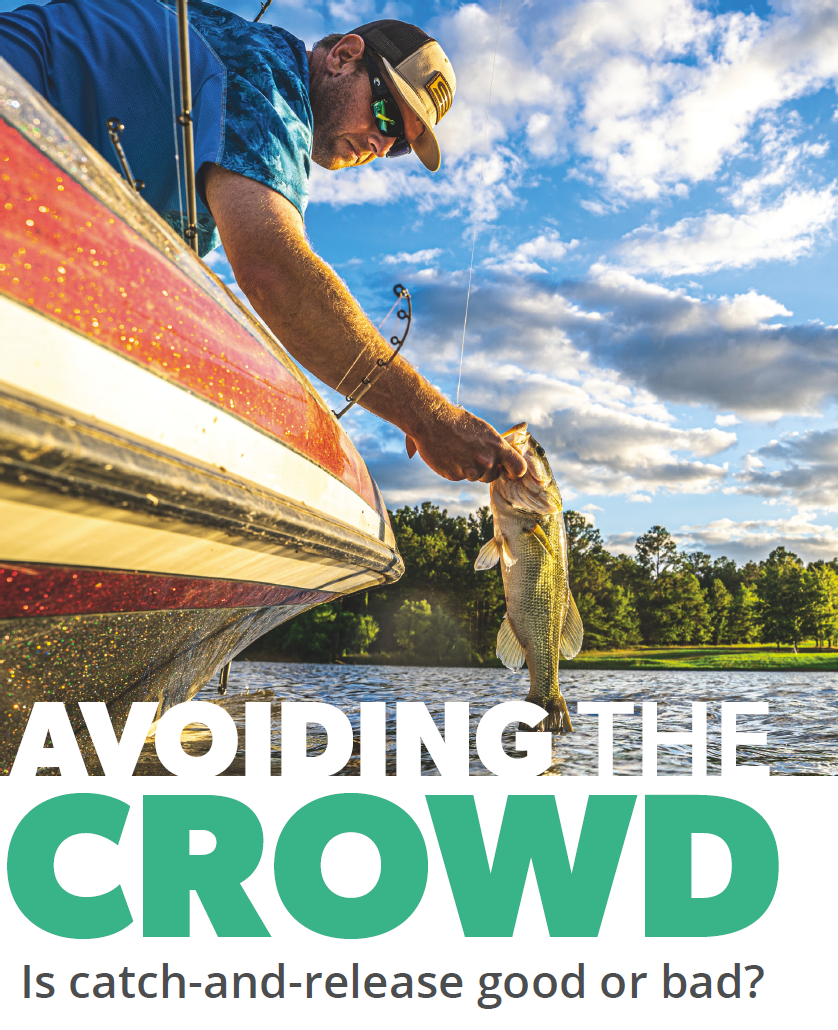

Avoiding the Crowd

10/6/2020 9:53:14 AM

Story by Stephen J. Brown / Photos by Edward Wall

Lee Wulff, renowned author, fly angler, and foremost proponent of catch-and-release ethics, is commonly credited with the saying, “Game fish are too valuable to be caught only once.”

Catch-and-release, of course, is the conservation technique where fish are hooked, landed, and immediately released. The catch-and-release ethic in angling began in earnest in the 1930s within fly-fishing circles to ensure the sustainability of heavily fished trout and salmon fisheries.

Tournament bass anglers were introduced to the practice during the world championship of bass fishing at Lake Mead, Nevada, in 1971, where Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (BASS) founder Ray Scott unveiled his “Don’t Kill Your Catch” program. Conservation of bass populations was the goal of the new program. With the advent of aerated live wells in bass boats, the catch-and-release technique became a successful and common practice.

Studies have shown that more than 95% of black bass (largemouth, spotted, and smallmouth) caught in fisheries across the country are released. And annual angler creel surveys of Mississippi’s state fishing lakes and reservoirs have indicated similar release rates. Catch-and-release practices have been extremely successful in protecting black bass populations, perhaps too successful. Herein lies a dilemma: Fishery managers attempt to regulate and promote harvest to achieve sustainable healthy fisheries, while anglers have been historically conditioned, with good intent, against harvest.

A fishery is composed of three parts: fish, environment (water and habitat), and anglers. Fisheries biologists use a variety of techniques to manage each component of a fishery:

Adding fish (supplemental stocking), which often bolsters fisheries that experience high harvest rates.

Manipulation of fish habitat, such as vegetation management, which can help to sustain most fish populations.

Size-limit regulations, which constrain or encourage the removal of specific sizes of various game fish species.

As in all fisheries, there are two ways to remove fish from a population: natural mortality and angling mortality. Catch-and-release practices limit the effectiveness of harvest regulations because they eliminate most of the necessary angling mortality. Harvest is essential to maintain healthy bass populations in nearly all reservoirs and impoundments. In any given water body, there is a limited amount of resources to sustain the biomass of fish. Fish populations can have several small fish, a few large fish, or fish somewhere in between. Regular successful spawning in many bass fisheries makes harvest a necessity to prevent over-crowding and reduced growth rates.

One of the most common tools for creating and maintaining trophy bass fisheries is the utilization of a “trophy slot length limit,” which is the size range that prevents anglers from keeping fish. These are typically 16- to 22- or 24-inch slot length limits that allow anglers to keep fish below and above the slot. Harvest below 16 inches will thin out the numerous smaller fish, and allowing harvest above the slot length limit gives anglers the opportunity to take home the trophy bass of a lifetime. This practice deters bass crowding and allows the remaining fish to grow faster. Without harvest, the goal of sustaining trophy bass fisheries is nearly impossible. The main goal is to reduce the number of bass so those that remain have less competition for prey.

However, because the harvest of large-mouth bass has become extremely low, slot limits have become ineffective, and fishery managers must become proactive to prevent bass-crowded situations. One technique that has historically been used to alleviate bass-crowded populations is to reduce the number of young-of-the-year largemouth bass by applying rotenone (a fish toxicant) in the pond or lake shoreline habitats. This approach can be useful in smaller ponds by removing a year class of bass, allowing the fish already in the pond to utilize the available prey and, in turn, increase growth rates. There are drawbacks for shoreline rotenone: The method is costly for larger ponds and lakes and the application must be timed appropriately and precisely when small largemouth bass are inhabiting the shallow shoreline.

Another technique that Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks biologists use to prevent bass crowding in newly renovated state lakes is to modify initial stocking rates of largemouth bass and blue-gill. After a lake is renovated and refilled, it will experience what fishery managers call the new lake effect. This occurs when a surge of additional nutrients is provided by vegetation and detritus break down. These nutrients move up through the food chain and create an environment for faster growth of young fish. By stocking fewer large-mouth bass and more bluegill, fishery managers hope to allow enough reproduction to sustain the bass fishery while also extending the boom of bass growth that occurs as part of the new lake effect. This will provide anglers the opportunity to catch trophy largemouth bass over an extended period in the lifespan of the lake. The aforementioned methods provide only temporary solutions to bass populations that, without harvest, will inevitably become bass crowded. Consistent and ample harvest of large-mouth bass is the most effective sustainable solution to maintain robust largemouth bass populations over the long term.

When anglers harvest largemouth bass while adhering to size and creel limit regulations, they help sustain healthy bass populations. This practice provides an excellent opportunity to teach young anglers proper conservation ethics. Catching and keeping largemouth bass creates the occasion to learn how to clean, filet, and prepare fish for consumption that ultimately yields excellent tasty fare for the family dinner table. Harvest can also help in maintaining a healthy Mississippi angling population. So, on the next fishing excursion at your local lake, keep a few bass to assist fisheries biologists in managing the bass populations.

Stephen J. Brown is an MDWFP Fisheries biologist.