Big Reds Rising

10/16/2019 11:18:00 AM

By John N. Felsher

The water churned coppery red about 300 yards away as terrified mullets leaped to escape their pursuers. They could not evade the red horde for long.

The boat motored toward the commotion, and we rigged the largest topwater baits we could find. Coppery heads protruded above the surface, looking like mullets only much larger. As we approached, we hurled our baits in front of the bronze mass. Moments later, the surface exploded as if someone detonated underwater mines. The big fish stretched our lines in reel-screeching, adrenaline-pumping combat before we each eventually subdued a 25- to 30-pound redfish. Fewinland fishing experiences equal the savagery of a big redfish smashing a topwater bait.

“When we see big bull redfish in massive schools, we throw topwater baits over them,” said Bryan Cuevas with Team Megabite Charters in D’Iberville. “They’ll slam it. Big reds really explode on a topwater bait. People need to hang on to their rods when one of those big bulls hits. Sometimes, we’ll see two or three fish heading to the bait. Once a fish gets hooked, others try to take the lure out of its mouth.”

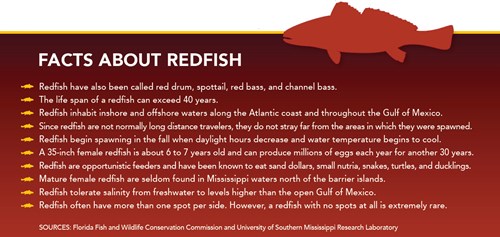

All along the Gulf Coast, giant bull redfish move toward shore to spawn from late summer through fall. Females release their eggs on incoming tides so the precious cargo can drift into the marshes and estuaries. Young redfish spend their first three to six years growing in the marshes before migrating offshore, where they will live for the rest of their lives. Some live longer than 40 years. When huge redfish return to the passes, bays and marshes each year, they give anglers outstanding opportunities for intensely exciting action.

When schools of rampaging bull reds enter the passes or inland waters, they can aggressively devour anything they can.

“On the Mississippi coast, we’ll see the ‘running of the bulls’ from about mid-July through the first cool snap in late October,” said Mark Wright with Legends of the Lower Marsh Charters in Pass Christian. “After redfish spawn, they follow the bait up into the marshes and estuaries. As the season progresses, schools become smaller.”

When schools of rampaging bull reds enter the passes or inland waters, they aggressively devour anything they can. They love munching menhaden (also called pogies), crabs, shrimp, and other baitfish. However, they hold an exceptional fondness for succulent mullets. Plankton-feeders, mullets generally stay near the surface and regularly stick their noses out of the water. A big topwater bait mimics a wounded mullet. Many anglers use baits in white or some combination of white and darker colors to imitate mullets.

“When those big bulls come inshore, they are feeding up for the spawn,” Wright said. “They will eat anything they can swallow. I’ve seen rats, seabirds, old bottle tops, fishing lures, and lots of other things in their stomachs. In the fall, mullets group up to spawn. We’ll see huge schools of them along the shorelines. We look for finger mullets about five to 10 inches long because that’s the size we usually find in redfish bellies. If I can find finger mullets or large concentrations of pogies in shallow water, that’s where I’ll fish.”

Anglers can use many surface attractants to tempt redfish all year long. Poppers, also called chuggers, float on the surface and make a popping commotion when an angler jerks a line. Prop baits are lures with small propellers attached on one or both ends that can thrash over the surface.

However, most saltwater anglers prefer “walking” baits for tempting reds on top. Worked with short, brisk wrist flicks, walking baits slide across the surface in a zigzag motion. Fish visually detect the movement and can feel the vibrations with their lateral lines. Many walking baits also come with internal rattles or clackers. Most fish, particularly redfish, can better hear low-frequency sounds, usually below 100 hertz.

“We walk baits with a repetitive twitch motion with a snap of the wrist so they zigzag from side to side,” Wright said. “Every bait has a different timing based upon its size, shape, and other factors. A redfish strikes more out of reaction to the action than homing in on a specific color. In low-light conditions, I throw black. On bright days, I throw white.”

Heavy walking baits sail long distances and cover water quickly, making them excellent search baits. Sometimes, a fish might follow a lure a long way before striking. Many people see the wake pushing toward the bait and pause the retrieve to let the fish catch up. With a hungry redfish on its tail, a baitfish never pauses but kicks in the turbo drive as it runs for its life. With a redfish approaching, move a bait slightly faster to simulate a baitfish trying to flee. Seeing its lunch trying to escape could enrage a spot-tailed beast so that the infuriated predator attacks with an even more malevolent strike.

“A redfish has no problem catching a bait if it wants it,” Cuevas said. “I usually work walking baits with a steady, side-to-side retrieve at a medium-slow pace.”

With downward-turned mouths better suited for slurping morsels off the bottom, redfish need to do some maneuvering to grab a topwater bait. They usually attack topwater temptations from behind with their heads out of the water or twist their bodies to get a better angle. Sometimes, they lose sight of their prey and miss.

Setting the hook too soon could pull the lure from its mouth. Keep moving the bait. The fish might come back to grab it or another redfish could hit it. Even when a fish grabs a topwater bait, pause a moment. Wait to feel the weight of the fish on the line. Then, set the hook hard. Some people set the hook again after starting to fight the fish. If fish keep striking at a bait but not taking it, downsize the offerings.

In weedy marshes, redfish often hunker down in thick cover or matted grass to ambush prey. Traditional hard baits cannot go through such cover. When entangling cover makes throwing conventional floaters impractical, switch to more subtle, soft-plastic lures. Rig them weightless with the hook points inserted into the plastic to make them snagless. Fish soft-plastic finesse baits such as lizards, flukes, or jerk shads over grass tops with a slow retrieve. Pause frequently. At tiny openings, let baits sink a foot or two before resuming the retrieve.

“Smaller, slot-sized redfish are more structure oriented than larger fish,” Wright said. “I like to find a good marshy shoreline with clumps of oyster shells where redfish can hide and ambush bait. In the marshes, I also look for points, cuts, pilings, riprap, and any other structure that might hold bait. Sometimes we fish the beaches from mid-summer to early fall. Off the beaches, we fish several artificial reefs about a half-mile or so from shore.”

(click to enlarge)

Many redfish anglers fish the marshes between Pearl River and Bayou Caddy near Waveland. The shorelines of Heron Bay hold good reds. Marshes surrounding Bay St. Louis can also provide great action in the fall. The Jourdan River and Bayou La Croix flow into the bay from the west, while the Wolf River enters from the east. Each stream feeds a fertile delta marsh. Anglers catch bull reds near the U.S. Highway 90 bridge or a railroad trestle crossing the bay close to its opening to Mississippi Sound. The barrier islands can also provide great action for bull reds.

“The barrier islands are excellent places to fish in September or October,” Wright said. “Cat Island also has some marshes that hold redfish. In the fall, shrimp migrate back into the estuaries. Redfish, trout, and other fish follow the shrimp. The marshes at the upper end of Bay St. Louis, where the Jourdan and Wolf rivers hit the bay, can produce good redfish action. The mouths of any bayous or rivers feeding into the bays should produce some good redfish. We’ll also fish around the harbors in three to four feet of water.”

The Tchoutacabouffa and Biloxi rivers feed into Back Bay, also called Biloxi Bay. Old Fort Bayou flows into the eastern side of the bay. The shallow bay also contains numerous islands, pilings, reefs, and other structures that hold fish. Like at Bay St. Louis, many people also fish the bridges near the mouth of Biloxi Bay for bull reds in the fall. Near Moss Point, the Pascagoula River creates a rich marsh delta that holds abundant redfish.

“From September through late fall, redfishing is on fire on the Mississippi coast,” Cuevas said. "In the fall and winter, people catch a lot of reds around the barrier islands by sight fishing. People also catch big redfish around the power lines in Biloxi Bay behind Keesler Air Force Base. I’ve had success fishing around pilings. Fort Bayou and the surrounding marshes are also good areas to look for reds. Bigger fish usually stay in the deeper water and come up into the shallows to feed as the bait moves through the bayou.”

From barrier islands to fertile delta marshes to sandy beaches and harbors, Mississippi offers anglers varied habitats to fish for redfish. Anglers just need to find baitfish. “Big reds” should not be far away.

John N. Felsher is a freelance writer for Mississippi Outdoors.