3/27/2020 9:57:13 AM

Jim Beaugez

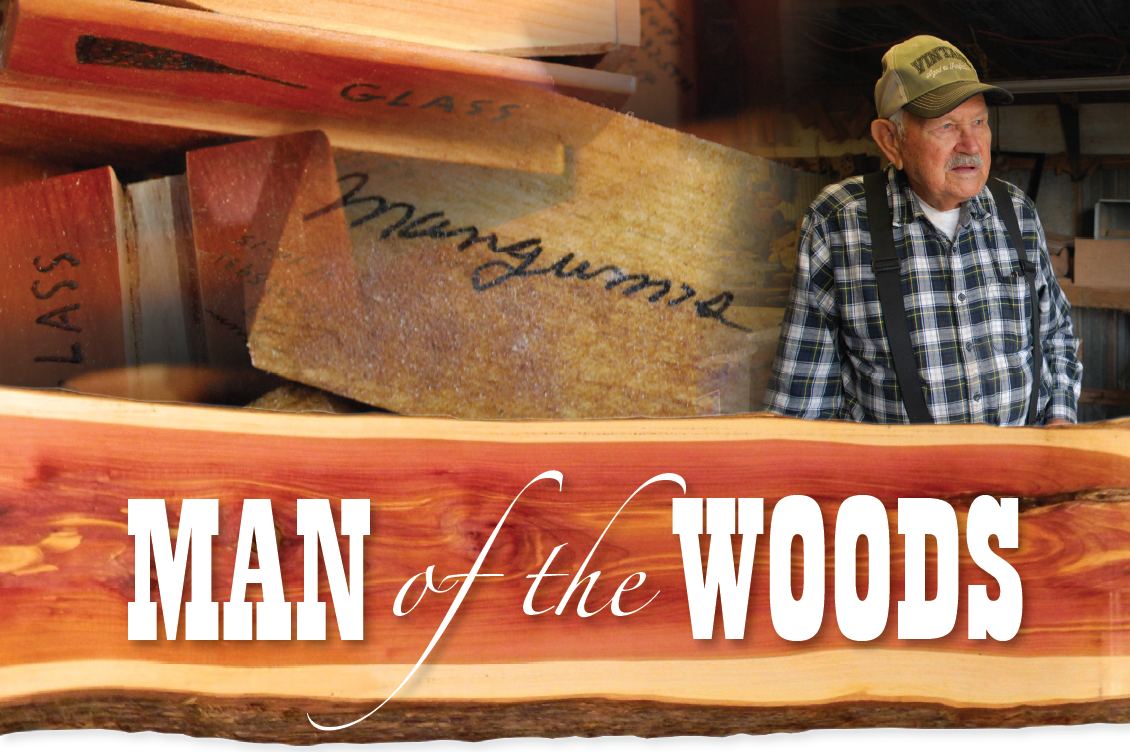

Ford Mangum has learned a lot about making and tuning turkey calls over the past 36 years. He picked up one of the most valuable lessons, though, not long after bringing his assortment of trough and box calls to market. And it had nothing to do with how they sound.

“Nobody knew (my calls) from Adam’s house cat, so the only way I could get (stores) to take ‘em was to put them on consignment,” the 91-year-old Mangum recalled. “I wasn’t making nothing out of that. You’d be surprised how many people went out of business or told me they’d been robbed or some big story to keep from paying for the calls.”

Mangum resolved to cut out the middle-man, opting to sell from his house through word of mouth and mail-order catalogs. But the products themselves served to be his best calling cards. Although by nature his handmade calls are all unique in subtle ways, they carry one common trait: his name and telephone number, inscribed on the top in his handwriting.

It has been his most valuable and consistent marketing tool. Since then, Mangum has fielded phone calls from all over the United States, talking through and then filling orders for turkey hunters who discovered his calls from a friend or an online forum or mail-order catalogs.

“When somebody calls me and wants a call, I try to pick out one of the best calls I got back there to send to him,” he said. “If I’ve got to make the judgment for him, I want it to be right. So I get a lot of self-satisfaction out of people still calling me.”

Word spread and phone calls came in from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and beyond. One hunter from Colorado came across them in Mexico when a guide used a Mangum aluminum trough call to coax a turkey down from an adjacent mountainside.

“He said the ol’ bird was up on the mountain, but he couldn’t hear (him) yelping. So (the guide) pulled out a call and started cuttin’ on that thing, and the turkey started raising his head, and he came right on down.”

A man named Mark McPhail, who discovered Mangum’s trough calls at a shop in Collinsville, had hunted with the same outfit in the mountains of Sonora, Mexico. He gave that call to his guide. An avid collector and now a builder himself, McPhail estimates that about 100-125 of the 3,700 calls in his collections are Mangum’s, including multiples of every call he has produced. On his hunting trip to Mexico, he bagged his three-turkey limit in five and a half hours with his favorite Mangum slate call.

“(The slate call) resonates,” says McPhail. “It's voicey. You can call very soft on it, you can cluck, purr, (or) cut. I've called up several hundred birds with that call. It's my go-to call. Always has been.”

At his home in rural Scott County, Mang-um eases down onto an upturned bucket. Next to him hangs the sturdy chains he once used to hoist engines and big-rig radiators for repair, a business he closed after hitting his stride with turkey calls. The open lean-to is built onto the shed where he has made thousands of calls going back to his earliest experiments, where discarded lumber and vintage saws, sanders, and drill presses sit idle amid sawdust drifts.

Mangum was not always a turkey hunter, but he believes he merely has an ear for it. He hunted quail and squirrel all his life, and then picked up deer hunting once the bucks returned to the swamps around Caney Creek. His son preferred hunting turkey, though, and finally brought his father around to his passion in 1983. That first year, using a Lynch box call, Mangum put turkeys on the ground. His interests quickly expanded from just hunting the birds to experimenting with making box calls himself.

“After Mr. Lynch died, (they) started mass production,” he said. “You can’t mass (produce) and have a good turkey call, because it’s hard enough when you work with them like I work with these, one on one. Still, if I can do 80-85%, I’m a pretty good call maker. If you’re mass (producing), you’re not going to get over 50%.”

Mangum picked up inspiration and tips from other calls he heard and how turkeys sound in the woods. He was drawn to the “big, deep-throated sound” of a box call his friend picked up from an old hunter, and a trough-style call he bought from a maker in Alabama. The sound was too tight and high-pitched for him, but he found a way to mellow it and kept building and improving his techniques until he got the sound right. The thickness and wood type all affected the sound.

“Back then there was a lot of cedars in there, and I found a log laying on the ground,” he said. “It wasn’t real big, but it was dry and hard. We were going huntin’ over there that afternoon, so I said, ‘I’m (going to) take this buck saw with me and saw me a piece of that cedar off and see if I can make a (box) call that sounds like I want it to sound.’ Man, I killed some turkeys with that call.”

He experimented with cherry, black walnut, and other local woods, but kept coming back to the cedar and poplar. Once he settled on that combination, he would get a local logger to drop off the logs he preferred.

“We’ve learned over the years what to use and what not to use,” Mangum said. “With the poplar, we always wanted the first cut outside of the heart. The heart can get kind of hard and all, but (just outside) it softens up. It had that yellowish tint to it. Now in cedar, you can look at it. That real dark cedar doesn’t work as well as that kind of light-tint cedar.”

Mangum went to market in 1999 when he had made up 500 box and trough calls, and sold them all within a couple of years. A heart attack that first year set him back six months, but he came back strong as interest in his calls grew. His glass and aluminum trough calls, like the one the hunting guide in Mexico used to pull that turkey down the ridge, have been his most popular sellers.

“A glass call will yelp in any kind of weather,” he explained. “If you’re using a slate, you get up on a bad humid morning, maybe a little fine, foggy mist, you’ve got to have a little experience just to use a slate call because it’s (going to) act up a little on you. But that glass won’t do it. You take that coarse sandpaper and stroke it, I guarantee, I don’t care what kind of morning, it’ll yelp.”

But, he added, “I like ’em all, and I use ’em all, (and) I’ve killed turkeys with all of them. But if I knew I could just have one and none of the rest of ‘em, it would have to be a glass call. It’s the most versatile.”

For most of the past three decades, Mangum has made and sold between 100 and 200 trough calls every year. In 2012, at 83, he placed fourth overall in the trough call division at the National Wild Turkey Federation call-making competition in Nashville.

Because of health issues, Mangum did not make any calls last year and has sold most of what he had. By his estimation, Mangum has fewer than 20 calls left in inventory. He says he would like to make more this year if he feels up to it. He still gets around, though, and hunts turkeys with the same Remington 1187 model 12-gauge shotgun he bought when he first started.

Mangum says his son builds a few calls periodically, and he hopes his grandson will pick it up one day. But if he’s made his last calls himself, Mangum is OK with that.

“I’ve (sold) enough to satisfy me.”

Jim Beaugez is a freelance writer for Mississippi Outdoors