7/8/2020 3:05:07 PM

By Rick Hamrick, Small Game Program Leader, and Adam B. Butler, Turkey Program Coordinator for MDWFP

Quality habitat allows nesting game birds, such as wild turkeys and quail, to remain concealed and avoid detection by employing their camouflage and natural instinct to remain motionless. When quality nesting habitat is well distributed, it can increase production and recruitment of new birds into the population. Recruiting as many new birds as possible is critical to balance out annual losses and buoy sustainable populations.

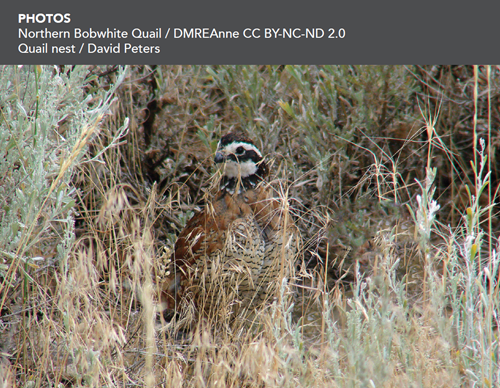

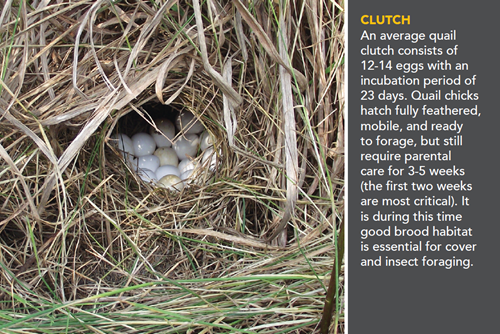

Threats lie around every corner for quail and turkey. Predation shapes their populations, especially during their nesting seasons. Once they begin incubating their nests, turkey and quail spend several weeks on the ground, anchored to one place, with only a few short recesses during the day to hurriedly feed. This period lasts 23 days for quail and 28 days for turkeys. Either way — a time of constant danger for expectant mothers and their developing eggs.

Many factors act in concert to determine a nest’s fate, and most are beyond the control of wildlife managers. Inclement weather, for example, can reduce the odds of success by causing hens to be more easily detected by scent-hunting predators. Nonetheless, nesting habitat can be enhanced, which ups the odds of nest success.

Nesting and brood-rearing

Although there is considerable overlap of their needs, quail and turkeys differ somewhat in their preferences for nesting habitat. Of the two, quail needs are probably more specific. Quail nesting habitat is typically characterized by perennial, native bunch grasses like broomsedge and little bluestem. This type of cover is provided when areas with these grasses have been left undisturbed from disking, mowing, or prescribed burning for several years. This creates a structured environment in which quail can build a well-concealed nest at the base of a clump of taller grass. Sometimes they will build nests in other litter like pine straw. Most quail nests are found in grassy fields, right-of-ways, or cutovers in their first few years of growth.

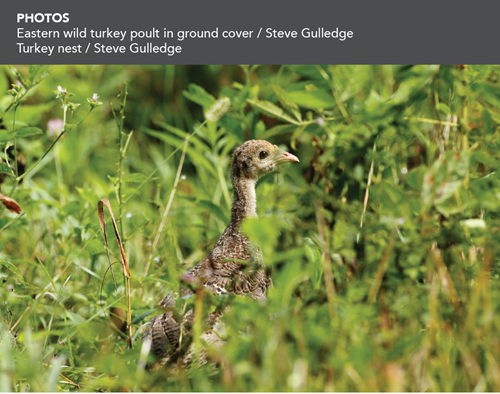

Wild turkeys tend to be more flexible with their nesting needs and choose sites with a more developed shrub component. This type of cover is often available several years after a disturbance, such as prescribed fire or timber clear-cutting. Turkeys tend to place their nests near the base of trees or adjacent to a log or other downed woody debris. However, turkeys will choose other areas, too, such as pastures or utility rights of ways. Turkeys are also more likely than quail to nest in heavily wooded areas. In areas with regular, active forest management, nesting cover for turkeys is rarely limited.

For both species, it is short-sighted to discuss nesting cover without considering brood-rearing habitat, which is the place where birds raise their young. The young of both species can immediately leave their nests to follow their mothers (sometimes their fathers, in the quail’s case) and feed themselves, which makes brooding habitat critically important. For both species, this habitat component is usually in short supply and is an area where the needs of the two species overlap completely. Brood habitat for both turkey and quail is characterized by an abundance of annual plants such as ragweed, partridge pea, and other broadleaf weeds that grow up to cover bare ground underneath. Good brood habitat is typically provided within one to two years of the soil being disturbed by disking or prescribed burning. Lack of brood habitat is arguably the single-biggest limiting factor for both turkeys and quail.

Proper arrangements

The arrangement of nesting and brood-rearing habitat is also important. Ideally, these should be provided relatively close together for newly hatched young birds to easily move from the relatively thicker nesting areas to nearby brooding habitat, characterized with more bare ground and umbrella-like overhead plant cover. Bare ground allows the small birds to move about freely and feed on insects while being concealed from predators. The open structure of brood habitat also potentially allows the young to remain drier on dewy mornings. This is especially important for quail because, even during summer, down-covered chicks can be at risk of hypothermia when they get wet.

Without habitat management or naturally occurring environmental disturbances, the quality of nesting and brood-rearing habitats quickly declines. Prescribed burning and disking are good management practices to maintain the appropriate plant community structure and composition of nesting and brooding habitat. Disking treatments to manage native vegetation in areas like old fields are best applied between October and February. Prescribed burning can be applied in a patchwork throughout the year to manage vegetation. Selective herbicides are useful for controlling undesirable woody brush that cannot be satisfactorily controlled by prescribed burning and disking. Mowing or clipping can be useful to prepare sites for other treatments, such as disking or maintaining some trails, but mowing does not usually produce good brood-rearing conditions as a standalone practice. These habitat manipulations are best implemented on a two to three-year rotation to manage nesting and brood-rearing cover — more frequently for quail and less frequently for turkeys. This suggests a half to a third of upland habitat patches should be manipulated in some way each year to maintain desirable vegetation.

By managing for quality nesting and brood-rearing habitats, we can help set the stage for successful reproduction to ensure the yearly cycle continues as efficiently as possible. Depending on our specific gamebird management goals, success can be measured in future gobbles, whistles, or a combination thereof.

Rick Hamrick is Small Game Program Leader and Adam B. Butler is Turkey Program Coordinator for MDWFP.